Chronique:Halo Bulletin 28/12/2011

28 décembre[modifier le wikicode]

Original[modifier le wikicode]

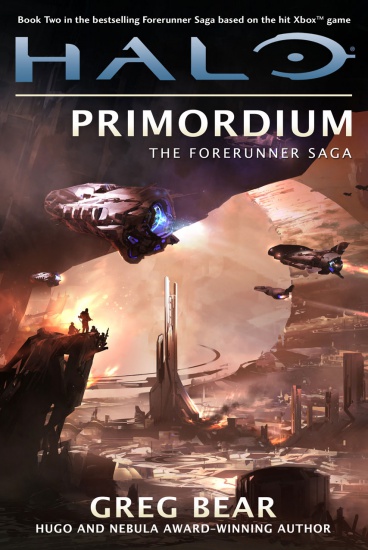

Some people have the day off, others are in the middle of their early-morning pre-lunch break, and a few rather dedicated souls are maintaining their normally busy schedule. Regardless of which group is applicable to your particular situation, we’re hoping all of you have enough free time to indulge in a little Halo-related reading because we have a treat for you today in the form of an exclusive book excerpt. Written by legendary science fiction author Greg Bear, Halo: Primordium is the second novel in the Halo Forerunner Saga, and the following is not just chapter two but also chapter three and part of chapter four of this soon-to-be-released book.

You can visit http://www.tor.com/ to get access to the prologue and chapter one. Then, come back here for the following few chapters. Halo: Primordium in its entirety will be released January 3, 2012. Enjoy the sneak peek!

TWO

HOW I WISH I could recover the true shape of that young human I was! Naïve, crude, unlettered, not very clever. I fear that over the last hundred thousand years, much of that has rubbed away. My voice and base of knowledge has changed—I have no body to guide me—and so I might seem, in this story, as I tell it now, more sophisticated, weighted down by far too much knowledge.

I was not sophisticated—not in the least. My impression of myself in those days is of anger, confusion, unchecked curiosity—but no purpose, no focused ambition.

Riser had given me focus and courage, and now, he was gone.

When I was born, the supreme Lifeshaper came to Erde-Tyrene to touch me with her will. Erde-Tyrene was her world, her protectorate and preserve, and humans were special to her. I remember she was beautiful beyond measure, unlike my mother, who was lovely, but fairly ordinary as women go.

My family farmed for a while outside of the main human city of Marontik. After my father died in a knife fight with a water baron’s thugs, and our crops failed, we moved into the city, where my sisters and I took up menial tasks for modest pay. For a time, my sisters also served as Prayer Maidens in the temple of the Lifeshaper. They lived away from Mother and me, in a makeshift temple near the Moon Gate, in the western section of the Old City….

But I see your eyes glazing over. A Reclaimer who lacks patience! Watching you yawn makes me wish I still had jaws and lungs and could yawn with you. You know nothing of Marontik, so I will not bore you further with those details.

Why are you so interested in the Didact? Is he proving to be a difficulty to humans once again? Astonishing. I will not tell you about the Didact, not yet. I will tell this in my own way. This is the way my mind works, now. If I still have a mind.

I am moving on.

After the Librarian (I was only an infant when I saw her) the next Forerunner I encountered was a young Manipular named Bornstellar Makes Eternal Lasting. I set out to trick him. It was the worst mistake of my young life.

Back before I met Riser, I was a rude, rough boy, always getting into trouble and stealing. I liked fighting and didn’t mind receiving small wounds and bruises. Others feared me. Then I started having dreams that a Forerunner would come to visit me. I made my dream-self attack and bite him and then rob him of the things he carried—treasure that I could sell in the market. I dreamed I would use this treasure to bring my sisters back from the temple to live with us.

In the real world, I robbed other humans instead.

But then one of the chamanune came to our house and inquired after me. Despite their size, chamanush were respected and we rarely attacked them. I had never robbed one because I heard stories that they banded together to punish those who hurt them. They slipped in, whispering in the night, like marauding monkeys, and took vengeance. They were small but smart and fierce and mostly came and went as they pleased. This one was friendly enough. He said his name was Riser and he had seen someone like me in a dream: a rough, young hamanush who needed his guidance.

In my mother’s crude hovel, he took me aside and said he would give me good work if I didn’t cause trouble.

Riser became my boss, despite his size. He knew many interesting places in and around Marontik where a young fellow such as myself—barely twenty years old—could be usefully employed. He took a cut of my wages, and his clan fed my family, and we in turn protected his clan from the more stupid thugs who believed that size mattered. Those were exciting times in Marontik. By which I mean, stupid cruelties were common.

Yes, chamanush are human, though tinier than my people, the hamanush. Indeed, as your display now tells you, some since have called them Florians or even Hobbits, and others may have known them as menehune. They loved islands and water and hunting and excelled at building mazes and walls.

I see you have pictures of their bones. Those bones look as if they might indeed fit inside a chamanush. How old are they?

*INTERRUPTION*

MONITOR HAS PENETRATED AI FIREWALL

AI RECALIBRATION

Do not be alarmed. I have accessed your data stores and taken command of your display. I mean no harm . . . now. And it has been ever so long since I tasted fresh information. Curious. I see these pictures are from a place called Flores Island, which is on Erde-Tyrene, now called Earth.

In reward for their service, I can now see that the Lifeshaper in later millennia placed Riser’s people on a number of Earth’s islands. On Flores, she provided them with small elephants and hippos and other tiny beasts to hunt…. They do love fresh meat.

If what your history archives tell me is correct, I believe the last of Riser’s people died out when humans arrived by canoe at their final home, a great island chain formed by volcanoes that burned through the crust….

I see the largest of those islands is known as Hawaii.

I am getting distracted. Still, I notice you are no longer yawning. Am I revealing secrets of interest to your scientists?

But you are most interested in the Didact.

I am moving on.

Soon after Riser took charge of my life, following a decline in our work opportunities, he began to direct his attentions toward preparing for “a visitor.”

Riser told me he had also seen a young Forerunner in a dream. We did not discuss the matter much. We did not have to. Both of us lay under thrall. Riser had met male Forerunners before; I had not. He described them to me, but I already saw clearly enough what our visitor would look like. He would be a young one, a Manipular, not fully mature, perhaps arrogant and foolish. He would come seeking treasure.

Riser told me that what I was seeing in my dreams was part of a geas—a set of commands and memories left in my mind and body by the Lifeshaper who touches us all at birth.

As a general rule, Forerunners were shaped much like humans, though larger. In their youth they were tall and slender, gray of skin, and covered nape, crown, shoulders, and along the backs of their hands with a fine, pale fur, pinkish purple or white in color. Odd-looking, to be sure, but not exactly ugly.

The older males, Riser assured me, were different—larger, bulkier, less human-looking, but still, not exactly ugly. “They are a little like the vaeites and alben that come in our eldest dreams,” he explained. “But they are still mighty. They could kill us all if they wanted to, and many would….”

I took his meaning right away, as if somewhere within my deep memory, I knew it already.

The Manipular did indeed arrive on Erde-Tyrene, seeking treasure. He was indeed foolish. And we did indeed provide him with what he sought—guidance to a source of mysterious power. But where we took him was not a secret Precursor ruin.

Following our geas, we led Bornstellar into the inland wastes a hundred kilometers from Marontik to a crater filled with a freshwater lake. At its center this crater held a ring-shaped island, like a giant target waiting for an arrow to fly down from the gods. This place was legendary among the chamanune. They had explored it many times and had built trails and mazes and walls across its surface. At the center of the ring-shaped island stood a tall mountain. Very few chamanush had ever visited that mountain.

As the days passed, I came to realize that despite my urges, I could not hurt this Manipular—this young Forerunner. Despite his irritating manner and obvious feeling of superiority, there was something about him that I liked. Like me, he sought treasure and adventure, and he was willing to do wrong things.

Meeting him, I began my long fall to where I am now—what I am now.

The Didact was in fact the secret of Djamonkin Crater. The ring-shaped island was where the Librarian had hidden her husband’s warrior Cryptum, a place of deep meditation and sanctuary—hidden from other Forerunners who were seeking him, for reasons I could not then understand.

But now the time of his resurrection had come.

A Forerunner had to be present for the Cryptum to be unsealed. We helped Bornstellar raise the Didact by singing old songs. The Librarian had provided us with all the skills and instincts we needed, as part of our geas.

And the Didact emerged from his long sleep. He plumped out like a dried flower dipped in oil.

He rose up among us, weak at first and angry.

The Librarian had left him a great star boat hidden inside the central mountain. He kidnapped us and took us aboard that star boat, along with Bornstellar. We traveled to Charum Hakkor, which awoke another set of memories within me . . . then to Faun Hakkor, where we saw proof that a monstrous experiment had been carried out by the Master Builder.

And then the star boat flew to the San’Shyuum quarantine system. It was there that Riser and I were separated from Bornstellar and the Didact, taken prisoner by the Master Builder, locked into bubbles, unable to move, barely able to breathe, surrounded by a spinning impression of space and planet and the dark, cramped interiors of various ships.

Once, I caught a glimpse of Riser, contorted in his ill-fitting Forerunner armor, eyes closed as if napping, his generous, furred lips lifted at the corners, as if he dreamed of home and family…. His calm visage became for me a necessary reminder of the tradition and dignity of being human.

This is important in my memory. Such memories and feelings define who I once was. I would have them back in the flesh. I would do anything to have them back in the flesh.

Then what I have already told you happened, happened.

Now I will tell you the rest.

THREE

THE HUTS STOOD on a flat stretch of dirt and dry grass. A few hundred meters away was a tree line, not any sort of trees I recognized, but definitely trees. Beyond those trees, stretching far toward the horizon-wall and some distance up the thick part of the band, was a beautiful old city. It reminded me of Marontik, but it might have been even older. The young female told me that none of the People lived there now, nor had they lived there for some time. Forerunners had come to take away most of the People, and soon the rest decided the city was no longer a safe place.

I asked her if the Palace of Pain was in this city. She said it was not, but the city held many bad memories.

I leaned on the girl’s shoulder, turned unsteadily—and saw that the trees continued in patches for kilometer after kilometer along the other side of the band, for as far as the eye could see . . . grassland and forest curving up into a blue obscurity—haze, clouds.

The young woman’s hand felt warm and dry and not very soft. That told me she was a worker, as my mother had been. We stood under the blue-purple sky, and she watched me as I turned again and again, studying the great sky bridge, caught between fear and marvel, trying to understand.

Old memories stirring.

You’ve seen a Halo, haven’t you? Perhaps you’ve visited one. It was taking me some time to convince myself it was all real, and then, to orient myself. “How long have you been here?” I asked her.

“Ever since I can remember. But Gamelpar talks about the time before we came here.”

“Who’s Gamelpar?”

She bit her lip, as if she had spoken too soon. “An old man. The others don’t like him, because he won’t give them permission to mate with me. They threw him out and now he lives away from the huts, out in the trees.”

“What if they try—you know—without his permission?” I asked, irritated by the prospect, but genuinely curious. Sometimes females won’t talk about being taken against their will.

“I hurt them. They stop,” she said, flashing long, horny fingernails.

I believed her. “Has he told you where the People lived before they came here?”

“He says the sun was yellow. Then, when he was a baby, the People were taken inside. They lived inside walls and under ceilings. He says those People were brought here before I was born.”

“Were they carried inside a star boat?”

“I don’t know about that. The Forerunners never explain. They rarely speak to us.”

Turning around, I studied again the other side of the curve. Far up that side of the curve, the grassland and forest ran up against a border of blocky lines, beyond which stretched austere grayness, which faded into that universal bluish obscurity but emerged again far, far up and away, along that perfect bridge looping up, up, and around, growing thinner and now very dark, just a finger-width wide—I held up my finger at arm’s length, while the female watched with half-curious annoyance. Again, I nearly fell over, dizzy and feeling a little sick.

“We’re near the edge,” I said.

“The edge of what?”

“A Halo. It’s like a giant hoop. Ever play hoop sticks?” I showed how with my hands.

She hadn’t.

“Well, the hoop spins and keeps everyone pressed to the inside.” She did not seem impressed. I myself was not sure if that indeed was what stuck the dirt, and us, safely on the surface. “We’re on the inside, near that wall.” I pointed.

“The wall keeps all the air and dirt from slopping into space.”

None of this was important to her. She wanted to live somewhere else but had never known anything but here. “You think you’re smart,” she said, only a touch judgmental.

I shook my head. “If I was smart, I wouldn’t be here. I’d be back on Erde-Tyrene, keeping my sisters out of trouble, working with Riser….”

“Your brother?”

“Not exactly,” I said. “Short fellow. Human, but not like me or you.”

“You aren’t one of us, either,” she informed me with a sniff. “The People have beautiful black skins and flat, broad noses. You do not.”

Irritated, I was about to tell her that some Forerunners had black skins but decided that hardly mattered and shrugged it off.

FOUR

ON OUR SECOND outing, we stopped by a pile of rocks and the girl found a ready supply both of water from a spring and scorpions, which she revealed by lifting a rock. I remembered scorpions on Erde-Tyrene, but these were bigger, as wide as my hand, and black—substantial, and angry at being disturbed. She taught me how to prepare and eat them. First you caught them by their segmented stinging tails. She was good at that, but it took me a while to catch on. Then you pulled off the tail and ate the rest, or if you were bold, popped the claws and body into your mouth, then plucked the tail and tossed it aside, still twitching. Those scorpions tasted bitter and sweet at the same time—and then greasy-grassy. They didn’t really taste like anything else I knew. The texture—well, you get used to anything when you’re hungry. We ate a fair number of them and sat back and looked up at the blue-purple sky.

“You can see it’s a big ring,” I said, leaning against a boulder. “A ring just floating in space.”

“Obviously,” she said. “I’m not a fool. That,” she said primly, following my finger, “is toward the center of the ring, and the other side. The stars are there, and there.” She pointed to either side of the arching bridge. “Sky is cupped in the ring like water in a trough.”

We thought this over for a while, still resting.

“You know my name. Are you allowed to tell me yours?”

“My borrowing name, the name you can use, is Vinnevra. It was my mother’s name when she was a girl.”

“Vinnevra. Good. When will you tell me your true name?”

She looked away and scowled. Best not to ask.

I was thinking about the ring and the shadows and what happened when the sun went behind the bridge and a big glow shot out to either side. I could see that. I could even begin to understand it. In my old memory—still coming together, slowly and cautiously—it was known as a corona, and it was made of ionized gases and rarefied winds blowing and glowing away from the nearby star that was the blue sun.

“Are there other rivers, springs, sources of water out there?”

“How should I know?” she said. “This place isn’t real. It’s made to support animals, though, and us. Why else would they put juicy scorpions out here? That means there might be more water.”

More impressive by the moment! “Let’s walk,” I suggested.

“And leave all these scorpions uneaten?”

She scrambled for some more crawling breakfast. I left my share for her and walked around the rock pile, studying the flat distance that led directly to the near wall.

“If I had Forerunner armor,” I said, “I would know all these words, in any language. A blue lady would explain anything I ask her to explain.”

“Talking to yourself means the gods will tease your ears when you sleep,” Vinnevra said, coming up quietly behind me. She wiped scorpion juice from her lips and taunted me with one last twitching tail.

“Aii! Careful!” I said, dodging.

She threw the tail aside. “They’re like bee stingers,” she said. “And yes. That means there are bees here, and maybe honey.” Then she set out across the sand, dirt, and grass, which looked real enough, but of course wasn’t, because the Forerunners had made this ring as a kind of corral, to hold animals such as ourselves. And it cupped the sky—a still river of air on the inside. How humbling, I thought, but I don’t think my face looked humble and abject. It probably looked angry.

“Stop grumbling,” she said. “Be pleasant. I’ll take back my name and stitch your lips shut with dragonfly thread.”

I wondered if she was beginning to like me. On Erde-Tyrene, she would already be married and have many children—or serve the Lifeshaper in her temple, like my sisters.

“Do you know why the sky is blue?” I asked, walking beside her.

“No,” she said.

I tried to explain. She pretended not to be interested. She did not have to pretend hard. We talked like this, back and forth, and I don’t remember most of what we said, so I suppose it wasn’t important, but it was pleasant enough.

I could not avoid noticing that the angle of the sun had changed a little. The Halo was spinning with a slight wobble. Twisting. Whatever you call it when the hoop….

Precesses. Like a top.

The old memories stirred violently. My brain seemed to leap with the excitement of someone else, watching and thinking inside me. I saw diagrams, felt numbers flood through my thoughts, felt the hoop, the Halo, spinning on more than one axis…. What old human that came from, I had no idea, but I saw clearly that based on engineering and physics, a Halo would not be able to precess very quickly. Perhaps the Halo was slowing down, like a hoop rolling along…. When it starts to slow, it wobbles. I didn’t like that idea at all. Again, everything seemed to move under me, a sickening sensation but not real, not yet. Still, I felt ill. I dropped to my haunches, then sat.

I hadn’t earned any of this knowledge. Once more, I was haunted by the dead. Somebody else had died so that this knowledge would be left inside of me. I hated it—so superior, so full of understanding. I hated feeling weak and stupid and sick.

“I need to go back inside,” I said. “Please.”

Vinnevra took me back into the hut, away from the crazy sky. Except for us, the hut was empty. I was no longer much of a curiosity.

I sat on the edge of the platform of dried mud-brick. The young female sat beside me and leaned forward. “It’s been five days since you arrived. I’ve been watching over you ever since, to see if you’d live or die…. Giving you water. Trying to get you to eat.” She stretched out her arms and waggled her hands, then yawned. “I’m exhausted.”

“Thank you,” I said.

She seemed to be trying to decide something. Her manners and certain shyness would not allow her to just stare. “You lived inside . . . on Erde-Tyrene?”

“No. There’s a sky, ground, sun . . . dirt and grass and trees, too. But not like this.”

“I know. We don’t like it here, and not just because they take us away.”

Forerunner treachery . . .

I shook my head to clear away that strange, powerful voice. But the existence of that voice, and its insight, was starting to make a kind of sense. We had been told—and I still felt the truth of it—that the Lifeshaper had made us into her own little living libraries, her own collections of human warrior memory.

I recalled that Bornstellar was being haunted by a ghost of the living Didact, even before we parted ways. All of us— even he—were subject to deep layers of Lifeshaper geas.

Even though it looked as if I had fallen out of somebody’s pockets, I might still be under the control of the Master Builder. It made sense that if Riser and I had value, he would move us to one of his giant weapons, then return later to scour our brains and finish his work.

But there was no Riser. And no Bornstellar, of course.

I had an awful thought, and as I looked at the woman, my face must have changed, because she reached out to softly pat my cheek.

“Was the little fellow with me when I came here?” I asked. “The chamanush? Did you bury him?”

“No,” she said. “Only you. And Forerunners.”

“Forerunners?”

She nodded. “The night of fire, you all leaped through the sky like falling torches. You landed here, in a jar. You lived. They did not. We pulled you out of the broken jar and carried you inside. You were wearing that.” She pointed to the armor, still curled up on one side of the hut.

“Some sort of capsule,” I said, but the word didn’t mean much to her. Perhaps I had just been tossed aside. Perhaps I did not have any value after all. The people here were being treated like cattle, not valuable resources. Nothing was certain. What could any of us do? More than at any time before, my confusion flared into anger. I hated the Forerunners even more intensely than when I had seen the destruction of Charum Hakkor…

And remembered the final battle.

I got up and paced around in the hut’s cooler shade, then kicked the armor with my toe. No response. I stuck one foot inside the chest cavity, but it refused to climb up around me. No little blue spirit appeared in my head.

Vinnevra gave me a doubtful look.

“I’m all right,” I said.

“You want to go outside again?”

“Yes,” I said.

This time, under the crazy sky, my feet felt stable enough, but my eyes would not stop rising to that great, awful bridge. I still wasn’t clear what information any of these humans could provide. They seemed mostly cowed, disorganized, beaten down—abused and then forgotten. That had made them desperate and mean. This Halo was not the place where I wished to end my life.

“We should leave,” I said. “We should leave this village, the grassland, this place.” I swung my arm out beyond the tree line. “Maybe out there we can find a way to escape.”

“What about your friend, the little one?”

“If he’s here—I’ll find him, then escape.” Truly, I longed to start looking for Riser. He would know what to do. I was focusing my last hopes on the little chamanush who had saved me once before.

“If we go too far, they’ll come looking and find us,” Vinnevra said. “That’s what they’ve done before. Besides, there’s not much food out there.”

“How do you know that?”

She shrugged.

I studied the far trees. “Where there are bugs, there might be birds,” I said. “Do you ever see birds?”

“They fly over.”

“That means there might be other animals. The Life-shaper—”

“The Lady,” Vinnevra said, looking at me sideways.

“Right. The Lady probably keeps all sorts of animals here.”

“Including us. We’re animals to them.”

I didn’t know what to say to that. “We could hunt and live out there. Make the Forerunners look hard for us, if they want us. At least we wouldn’t be sitting here, waiting to be snatched in our sleep.”

Vinnevra now studied me much the same way I studied the distant trees. I was an odd thing, not one of the People, not completely alien. “Look,” I said, “if you need to ask permission, if you need to ask your father or mother . . .”

“My father and mother were taken to the Palace of Pain when I was a girl,” she said.

“Well, who can you ask? Your Gamelpar?”

“He’s just Gamelpar.” She squatted and drew a circle in the dirt with her finger. Then she took a short stick out of the folds of her pants and tossed it between two hands. Grabbing the stick and holding it up, she drew another circle, this one intersecting the first. Then she threw the stick up. It landed in the middle, where the two circles crossed. “Good,” she said. “The stick agrees. I will take you to Gamelpar. We both saw the jar fall from the sky and land near the village. He told me to go see what it was. I did, and there you were. He likes me to bring news.”

This outburst of information startled me. Vinnevra had been holding back, waiting until she had made some or other judgment about me. Gamelpar—the name of the old man no longer wanted in the village. The name sounded something like “old father.” How old was he?

Another ghost?

The shadow racing along the great hoop was fast approaching. In a few hours it would be dark. I stood for a moment, not sure what was happening, not at all sure I wanted to learn who or what Gamelpar was.

“Before we do that, can you take me to where the jar fell?” I asked. “Just in case there might be something I can find useful.”

“Just you? You think it’s about you?”

“And Riser,” I said, resenting her sad tone.

She approached and touched my face, feeling my skin and underlying facial muscles with her rough fingers. I was startled, but let her do whatever she thought she had to do. Finally, she drew back with a shudder, let out her breath, and closed her eyes.

“We’ll go there first,” she said. “And then I will take you to see Gamelpar.”